The poet Edward Dorn (1929-1999) was born in Illinois during the Great Depression, a fact that would mark him forever. Struggling through poverty as a child and into

adulthood, Dorn was intellectually hungry and dissatisfied with the status quo. His poetry and essays deal with the particular realities of North American identity, culture, and history, pushing poetic language into the darkest corners of experience. Dorn spent his life writing and teaching as he moved from town to town, particularly as a younger poet looking for work. Often considered a poet of the American West, Dorn also lived in England for several years during the latter half of the 1960s; he would eventually settle in Colorado, teaching at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

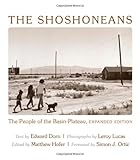

The Shoshoneans was the first work of Edward Dorn’s that I fell in love with. When I came across his stunning poem about his own family’s struggles, “On the Debt My Mother Owed Sears Roebuck,” it sent me on the way into an entirely new poetics and a love affair with Dorn’s words and ideas that still engulfs me. When I began looking for his work, The Shoshoneans: The People of the Basin-Plateau, the genre-breaking 1966 account of traveling through Shoshone lands with photographer Leroy Lucas had long been out of print, and I struggled to find even a used copy. When I finally did, it was an old library hardcover with no dust jacket, fraying, yellowed, and on the verge of falling apart (and expensive!). I read this work voraciously several times through, moved by the beauty of Dorn’s words, the beauty of Lucas’s photographs, and the sharp, unsentimental and complex ideas and observations put forth in the text.

In the newly reprinted edition of The Shoshoneans published by University of New Mexico Press last year, Simon J. Ortiz places the book firmly within the mid-1960s culture of Vietnam War resistance. Ortiz’s foreword sets the tone for thinking about this important book and its engagement with war in all its myriad forms in the context of North American culture and history. Taking on the codes of imperialism,

subjugation, and genocide, Dorn’s text and Lucas’s photographs force us to consider the consequences of war, the “full-scale invasion and occupation by Euro-Americans that comprised the colonization of the Americas,” as Ortiz puts it. This is a book that considers the long view of North American history and takes a hard look at some of the Indigenous people of this continent without romanticizing or flinching from what is found.

Covering several states where the Shoshone people have resided or continue to reside, including Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico, Dorn and Lucas drive their car, talking to people, listening to the stories people are willing to tell them. Dorn remains somewhat apart, feeling the weight of his own history and culture without quite knowing how to reconcile himself with the Shoshone with whom he comes into contact. He is traveling with Leroy Lucas (who was for a while known as Leroy McLucas, as the original prints of the book indicate), an African American man, a point noticed by every small town sheriff, bartender, and townsperson who sees them. Remember, it was 1966 when the gains of the Civil Rights movement had only just begun to be put in place by the law and were even further behind in actual practice. The pair were noticed wherever they traveled, their difference in skin color creating a buzz around them in a country struggling – often violently – with race.

The stories Dorn relays are personal and frequently uncomfortable. In the book’s opening scene, he writes: “I begin where it was the highest pitched for me, at Duck Valley, on the Nevada-Idaho border.” This was his meeting with the 102-year-old Willie Dorsey and his wife, who is left nameless and ageless, though Dorn describes her as “the oldest creature I ever saw.” Dorn confronts, with the Dorseys, himself: He doesn’t know how to react to their lives, their ancient years, their filth, their apparent hunger and poverty. Willie Dorsey points to a chair for Dorn, a chair so dirty that Dorn is flummoxed:

I felt crossed by an embarrassed confusion: what and who I was compressed all at once into one consideration, again I watched myself as I might think of a god watching, and there was in me at the same moment the hopelessly practical hesitation to soil my seat and the public willingness to do so – followed by a self-censure for having thought of it in either sense. The point in any case for me was moral. I must sit in this man’s refuse.

These are powerful words to begin this reading journey that we take with Dorn, anxious and conflicted. This anxiety seems right to me – the landscape of the Shoshone people that Dorn encounters is so unfamiliar to non-Indigenous North Americans, arriving at their present

lives from the other side of the war-spectrum, as it were. Dorn did not come to this journey as a rich or powerful man, in terms of culture or capital; he was a struggling poet and part-time teacher. Nor did he undertake this trip as a do-gooder or with illusions of saving anyone; he arrives as a writer first and foremost, someone interested in the complex history of his homeland. During a good part of the early 1960s, he had lived in Pocatello, Idaho, a town named for a Shoshone leader, Chief Pocatello, a leader in the fight against settlers. Dorn was a seeker, a poet turning over all the rocks and opening all the doors in order to see.

So many of the Shoshone people that Dorn and Lucas come into contact with are still clearly suffering the ravages of the war perpetrated against their ancestors and their very lands. Poverty and alcoholism run rampant. Throughout the 1960s, the Shoshone were being shipped off to fight in Vietnam and returning battered and changed – if they returned at all – and bearing the physical and psychological scars of battle. Dorn and Lucas listen to the men’s stories of having been “over there,” of having their cousins, friends, and brothers presently there. Many of the older Shoshone men had also been drafted or signed on to fight in the Korean War. They were returning to what were often impoverished circumstances, land that was too often bereft of a strong economy or agriculture, wearing the scars of the wars perpetrated against the Indigenous people of North America. Scene after scene in The Shoshoneans paints the landscape of left-behind peoples.

In Nixon, Nevada, Dorn finds a white-owned and -occupied bar on First Nation land (known then as a reservation). Knowing this can’t be right, he talks to an Indigenous man, asking about the situation, who indicates that the bar folks are simply squatters and there wasn’t

anything to be done about the situation. Dorn recounts their conversation, reporting his sense about what’s going on:

All life was a series of compromising effects for him, and that probably accounts for the innate hesitation of his reply. Although he didn’t say it, I could read it on his face: Whatever goes down, I won’t have any control over it and I (and my people) will have to get through it the best we can. For “get through” you might as well read “stay out of the way of it.” And I was thinking too, good God, how hopeless, it really doesn’t concern this man, he just lives his life along with it. Manifest Destiny, whether he’s heard of that or not, turns back in on him anyway, as much a domestic force as it is foreign, and the more it becomes frustrated and resisted abroad the more it turns back in, turns back into America.

This passage, I think, is really the center of what Dorn finds and is the crux of how he sees North American history and culture. The damages of war, whether hot or cold, are long lasting and treacherous. The Indigenous peoples that Dorn and Lucas find are rarely in a strong cultural, political, or economic position, and this weighs on Dorn, who cannot help but see the long and ugly history that led to

this moment. The Shoshoneans is filled with Dorn’s straightforward, uncompromising lament, a lament that, at the same time he feels it, he is conflicted about feeling it. His encounter with the Dorseys highlights this conflict – he can see the long path of history and the horrors it has wrought, but he is always aware that it is maybe not his place to speak of, or for, any Indian: “Whenever any non-Indian citizen presumes to speak to or about Indians, there is in his mouth a rather heavy inheritance of qualifying history: past, recent and – particularly – present.”

Lucas, on the other hand, has a different experience than Dorn, having experienced racism and exclusion as a Black man. Where Dorn remains outside, struggling with his thoughts on what he is seeing, Lucas is able to more fully immerse himself into the lives of the people they meet. He ultimately joins the sacred – and private – Sun Dance, and as Dorn points out, he comes out a changed person. The Sun Dance “is a technique for living. For the participant it is a form of worship. And it is a curative ceremony.” These sacred dances, elements of which have been handed down long before any European contact with the First Nations, began anew in the nineteenth century in an act of recovery against occupation and annihilation. The new North Americans attempted to suppress and halt the dances,

making them illegal, but by the mid-twentieth century they were being revived and regularly practiced again. Dorn does not participate; he writes about the history of the dances and he takes note of their significance and weight, including for his friend Lucas, but stands outside. That “heavy inheritance” is too much for him to be allowed inside, an inheritance Dorn perceives with great seriousness.

Dorn assumed, we might say, the role of town crier. He took on this role naturally, ordered, as it was, by his own sense of outrage at the complacency that comes with not speaking up. This position can signify difficulty and complexity; it requires an edge in thinking, an intellect we can lose, caught up in the middle of things. Stepping forward and away can lead to radical change, rupture, revolution. This, I think, is Dorn’s stance, consistently through his poetry and life. The political, academic and social games we play often keep many writers from speaking truthfully, but Dorn’s work defies the safe, the mediocre, and the middle ground. The Shoshoneans is a testament to the need for understanding what is ugly, difficult, and complex.

In the twenty-first century, terms and language have changed, in a practice that removes at least some of the shadows of war. Where Dorn uses the word Indian, presently we talk about Indigenous people; the word reservation has been removed: It is more appropriate to both talk and think about these spaces as Nations, which is what they are. While Dorn used the language of his own time, his discomfort is palpable. What Dorn found in his travels proved to be even more complicated than he might have expected. As Ortiz notes, “Ed offers almost no commentary or interpretation, nuanced or otherwise; his book details only the expository narrative.” Indeed, Dorn says, “I have no need or intention to deny the speciality of my own view of Indian people and their affairs. I am therefore pleased to give an American Indian the last word in this essay.” The strong, powerful essay which closes out the book, “Poverty, Community, and Power,” was written by Clyde Warrior, a youth movement leader, and gives voice to Indigenous concerns that Dorn knew was not his own place to speak. The Shoshoneans, however, is all of our place to read – it is one way in, one way back, and maybe even one way to recovery in a damaged place.

Claudia Moreno Parsons was born in Brooklyn, NY. She is an associate professor of English at LaGuardia Community Colllege, CUNY. She studied North American poetics and earned her PhD at the Graduate Center, CUNY. She is the editor of Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn: The Collected Letters (University of New Mexico Press). Her research is in North American literature, culture, and history, with specializations in poetics, the literature and politics of the 1950s and 60s, and women’s literature and history.