In August 1994, Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar traveled to Rwanda in the aftermath of the country’s infamous genocide. He documented scenes of murder, mass graves and refugee camps in Uganda and the DRC, which was then called Zaire. He interviewed, filmed and photographed survivors.

Jaar’s visit initiated The Rwanda Project, a six-year undertaking involving mixed-media installations responding to the spectre of genocide and the world’s collective failure to react.

Reflecting on the project, Jaar said, “I was shocked and appalled at the criminal indifference of the world community.” He continued, “It took a while to analyze and understand the information I accumulated. I felt blocked intellectually and shocked psychologically.”

Exercises of representation

The inability to encapsulate trauma led Jaar to test different ways of portraying genocide. Collectively, however, his ‘exercises’ navigated the ethics of representation and the aestheticization of suffering by defying the conventions of documentary photography. Unlike photojournalists and reporters at the time, Jaar refused to display images of victims themselves.

In Real Pictures, Jaar concealed sixty photographs taken in Rwanda inside black boxes arranged on the floor. The top of each box was inscribed with a caption describing the image within. By withholding the photographs, Jaar emphasized the impossibility of representing tragedy, while referencing the invisibility of the genocide in global media.

This emphatic absence was also referred to in (Untitled) Newsweek. Jaar exhibited the seventeen Newsweek magazine covers that coincided with the genocide in 1994, along with facts on the extent of violence in Rwanda. As reports suggested that thousands were being killed, the periodical gave prominence to stories on O.J. Simpson, Richard Nixon and Nelson Mandela.

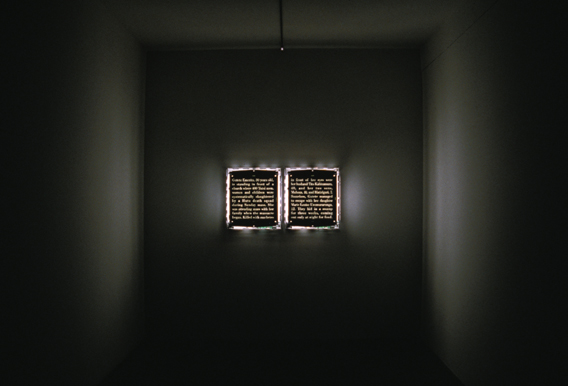

The Eyes of Gutete Emerita consists of backlit images of Emerita’s eyes and text recounting her personal story. Gutete Emerita managed to escape with her daughter from a church where 400 Tutsis were massacred. She was attending Sunday mass with her family and witnessed Hutu militia murder her husband and two sons with machetes.

For this piece, Jaar decided to reduce the scale of the genocide to a single human story. He felt that the idea of one million dead was an abstraction that failed to address the dimensions of suffering. Relaying Emerita’s experience through her eyes, the viewer is confronted with the act of witnessing and the cost of inaction.

The Silence of Nduwayezu played with the sense of scale itself. It consisted of a light table covered with one million identical slides of Nduwayezu’s eyes, each representing a murdered individual. Viewers were invited to examine the slides with a magnifying glass. Nduwayezu was a young refugee who witnessed his parents’ murder.

Complicity and humanitarian action

For Frank Möller, Jaar’s work is an example of how “to circumvent the looking/not looking dilemma and to increase the audience’s awareness of its own responsibility….[His] artwork haunts the viewer, not because it shows images depicting brutality but because it alludes visually to brutality only by implication.”1

By withholding images of atrocity, Jaar avoided photography’s tendency to aestheticize its subjects through framing and composition. Viewers, in turn, would not be complicit in the subjects’ suffering through the consumption of those images. Instead Jaar confronted the viewer to examine the collective indifference to human suffering without, he says, “falling into the trap of what media did or did not do.”

Two decades on, the questions on representation and humanitarian intervention seem as salient as ever. Citing the current situation in Syria, Jaar laments, “The world is as wicked as it was twenty years ago. We continue to ignore conflict, with ignorance and indifference. The world hasn’t managed to do anything. I am not hopeful.” - By Tyler Chau

Endnote

1. Möller, F. The looking/not looking dilemma. Review of International Studies, 781-794.

* * *

Alfredo Jaar

Field, Road, Cloud, 1997

Six C-prints

Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York, Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zürich, and the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar

The Eyes of Gutete Emerita, 1996

Two quadvision lightboxes with six b/w text transparencies and two color transparencies

Courtesy the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar

The Silence of Nduwayezu, 1997

One million slides, light table, magnifiers, illuminated wall text

Courtesy Galería Oliva Arauna, Madrid, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin and the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar

Untitled (Newsweek), 1994

Seventeen pigment prints

Courtesy Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg / Cape Town, Galerie Lelong, New York, kamel mennour, Paris, Galerie Thomas Schulte, Berlin, and the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar

Real Pictures, 1995

Color photographs in archival boxes, silkscreen

Courtesy Galerie Lelona, New York, Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne and the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar

Rwanda, Rwanda, 1994

Public intervention, Malmö, Sweden

Courtesy the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar

Signs of Light, 2000

Public intervention, Lyon

Courtesy the artist, New York

Alfredo Jaar is an artist, architect, and filmmaker who lives and works in New York. He was born in Santiago de Chile. His work has been shown extensively around the world. He has participated in the Biennales of Venice (1986, 2007, 2009), São Paulo (1985, 1987, 2010) as well as Documenta (1987, 2002) in Kassel. Important individual exhibitions include The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, Whitechapel, London, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, as well as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Rome and Moderna Museet, Stockholm. A major retrospective of his work took place in 2012 at three institutions in Berlin: Berlinische Galerie, Neue Gesellschaft für bildende Kunst e.V. and the Alte Nationagalerie. Last year Alfredo Jaar represented Chile at the 55th Venice Biennale. He has realized more than sixty public interventions around the world. He recently completed two important public commissions: The Geometry of Conscience, a memorial located next to the just opened Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago de Chile; and Park of the Laments, a memorial park within a park sited next to the Indianapolis Museum of Art. More than fifty monographic publications have been published about his work. He became a Guggenheim Fellow in 1985 and a MacArthur Fellow in 2000. In 2006 he received Spain's Premio Extremadura a la Creación.