Recent beheadings of foreigners held captive by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) have prompted several major media outlets to censor graphic scenes of death and violence. These outlets have refused to display images or footage that portray these deaths out of respect for victims’ families and a desire to avoid fueling ISIL’s propagandistic vision.

News outlets have nonetheless deployed imagery that implies imminent violence. A recent Daily Mail article in the UK, written after the killing of US aid worker Peter Kassig describes the verbal narrative of the execution video in detail and supplies several stills, some of which show the imminent deaths of Syrian soldiers included alongside the Kassig footage. Although the images included in the article refrain from outright gruesomeness, they display ISIL killers brandishing knives in the moments before execution, and are supplemented by suggestive captions such as: “Bloodthirsty: The video shows in full graphic detail how the militants saw the heads off their victims.” Horror is deferred but not refused.

Deferring the explicit violence of the ISIL videos suggests that we have not, in spite of Susan Sontag’s warning in On Photography (1977), become “utterly inured to the shock of images.” But that deferral does defuse the shock. We have, in our mind’s eye, already filled in the blank. This ostentatious absence has opened up a space for thinking about the expectations of spectatorship and the relation between visuality and documentation. Close scrutiny of the ISIL imagery has largely taken place out of public sight, confined to the closed quarters of expert institutions such as the National Center for Media Forensics in Denver, Colorado. This analysis has produced its own irony. Even as the expert mining of videos for hard evidence about the identity of the killers, captives, and locations confirms certain claims about the veracity of visual documentation, that same work has proven that some of the footage showing the beheadings was staged, exposing the fiction of “reality” in such documentation.

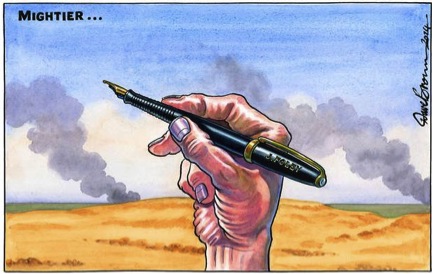

One of the most interesting and deeply humane responses to this renewed crisis of visual documentation is a cartoon by Dave Brown that appeared in British newspaper The Independent two days after the video of James Foley’s death emerged on August 19 of this year.

The drawing is powerful precisely because it incorporates desensitization into its visual rhetoric. Brown’s cartoon landscape is emptied out of meaning: plumes of smoke rise in the distance, the visual punctuation of an identikit warscape, of a somewhere that is not here; the flat horizon of vacant green land sits suspended between waves of rocky desert in the foreground and a cloudy haze merging into an upper atmosphere of blank sky.

Against this landscape, a hand rises from the ground. But this isn’t the exhausted visual trope of shock photographic reportage—the protruding body part, stiffened in rigor mortis, reaching out to our horror. Here the hand is sinewy, sharp-knuckled, and poised in a dexterous grasp. In these lively fingers rests a fountain pen inscribed with its owner’s name—J. Foley.

A more sentimental cartoonist might have left us with that frozen image, the hand on the cusp of putting pen to paper, about to fill the blank landscape with meaning. Instead the tip of the fountain pen directs the eye towards the top left corner of the cartoon, where “MIGHTIER…” is written in the sky. Pen has already been put to paper. The empty landscape has already been inscribed, aphoristically, with the power of language to make sense of the world. If James Foley’s name risks becoming the object of brutal violence in ISIL’s visual propaganda, this image guards against that reduction. The pen has already shown it is mightier than the sword.

One of the basic tensions within photojournalism is the uneasy relationship between image and language. Photojournalism requires some kind of narrativization—a caption, an embedding of images within a written report, or simply the expectation that a montage of images will create a “story” to be told inside one’s own head. Photojournalism depends on verbal narrative, but it also subjugates language to the affective pull of the image, its raison d’être.

Brown’s cartoon image similarly depends on language. The visual rhetoric doesn’t make any sense without the inclusion of the word “MIGHTIER…” and the inscription “J. Foley”, and it doesn’t make full sense if you don’t know the verbal expression, “the pen is mightier than the sword.” But the brilliance of the cartoon lies in the equivalency it establishes between image and word. There is no subjugation of one over the other; the drawing elevates both word and image into a moment of deep personal connection—an example in cartoon of what Roland Barthes called a photograph’s punctum. Most crucially, Brown’s image emphasizes the dignity and agency of James Foley and others like him, redirecting our gaze away from violent ends.

Online media and sites like Instagram, Facebook, and Tumblr are built to encourage the hypersaturation of images. Photojournalism from conflict zones is especially prone to this kind of inundation. Swiping and scrolling can create a kind of digital phenakistoscope in which individual images flash and ultimately blur into a new afterimage. When you combine this transient way of consuming images with the sophisticated digital manipulation that has made recent visual records of conflict in Gaza and Syria so problematic, the connection between viewing and objective truth seems especially fraught. Images like Brown’s cartoon arrest the flow. They break up the afterimage and make us look back. They do not simply refuse violence, or goad us into filling in the blank with the horror we have already imagined. They live past the imminence of violence.

Will Fysh is a PhD student and Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar in the History department at the University of Toronto. His research focuses on decolonization, international aid, and the ethics and politics of photographic witnessing during the long 1960s.

Cover image via The Daily Mail.