Nejla and Maya stand in their Istanbul bedroom clad in neon workout gear with a laptop open in front of them. A YouTube video shows a peppy yoga instructor and a posse of students behind her. The girls follow along with purpose as the teacher guides the virtual audience through each pose.

Since they left their home in Syria, this routine isn’t just a hobby for the Maya and Nejla—it’s sanity. It’s how they have learned to fill their time as refugees—a period that has now dominated a large part of their young lives. Lives of immobility. Shut in their room, if they’re not watching yoga, they’re practicing kick boxing—more cardio if they’re in the mood. Maya wipes the sweat from her forehead and opens the window to Istanbul’s orange light.

The same light shines into the temporary homes of other displaced people around the city. It drifts in through windows as the sound of late night WhatsApp and FaceTime conversations drift out—the virtual threads connecting Syrians separated by war’s forced diaspora. The nuances of their experiences are embedded in these snippets of phone messages and details on computer screens. These small mercies of technology help give order to lives disrupted and caught in stasis.

Maya and Nejla say nightly YouTube sessions help distract them from uncertainty. The girls are thirteen and fifteen. They were in primary school when their family left their home in Damascus. In the four years since then, YouTube lessons on their laptop have come to substitute for being back in the classroom. They have been stuck in Istanbul for nearly a year while applying for reunification with their mother in Sweden. They wait without a timeline.

These feelings of uncertainty are not uncommon for many of the other 400,000 Syrian refugees living in Istanbul. Coming from Syria, many hoped to move west as quickly as possible—stories of free housing in countries like Germany and Sweden more enticing than life without government support in Turkey. Since the beginning of Syria’s civil war in 2011, Turkey’s western coast has become a transit point for those attempting to travel without government-sanctioned ways to Europe.

Nejla, 13, lived in Istanbul eight months with her father waiting for word from the Swedish embassy about reuniting with her mother and little sister in Europe. Not enrolled in school, she fills her time watching YouTube videos and connecting with Swedish people on social media in anticipation of a new beginning in Europe.

Fatima lives with seven family members in a small apartment after fleeing Aleppo when their home was bombed. Fatima spends her time in Istanbul sewing dresses inside her home to help support her mother and siblings after her father traveled on to Germany to apply for refugee status. The family remains separated with few options for resettlement.

The trip from Turkey to Europe by sea is costly and unpredictable—something Mohammad knows all too well. Since coming to Turkey, he has become part of the smuggling network responsible for organizing transport of refugees to Europe. Sitting at a café in Istanbul, he checks his iPhone obsessively with one hand while sipping Turkish coffee shakily with the other. His job in the smuggler chain is coordinating—calling, texting and organizing payment for travel: around $1,000 per person.

Although the price tag for a future in Europe is hard to swallow, it’s all part of the business, Mohammad says. “Everybody knows the price. It’s routine. People trust me.” The job itself has its risks, once landing Mohammad in Turkish prison for six months, but it’s nothing compared to the gamble for refugees to get a spot on a smuggler’s inflatable boat. Traveling illegally is a tricky proposition. It requires many to pay for a fake passport and entrust money to smugglers at the risk of being cheated—not to mention losing their lives.

Smuggling isn’t something Mohammad planned on doing. He worked for the Zara retail store in Syria but in Turkey, like many, he found himself jobless and desperate. When offered money to help smuggle, he jumped at the opportunity, and has never had a shortage of customers. The International Organization of Migration (IOM) estimates that over 350,000 migrants entered Europe by sea in 2016. For many, possibilities across the Mediterranean represent a shining alternative to the challenges of life in Turkey.

However, an agreement between the European Union (EU) and Turkey in March 2016 has made traveling to Europe even more difficult. The agreement attempts to stem the flow of migrants from Turkey to Greece by sending illegal arrivals back to Turkey. In exchange, the EU vowed to increase resettlement of refugees already living in Turkey, but without creating incentives for those people to stay. The deal also promises avenues for Turkish nationals to get visas into the EU, an added incentive for Turkey as it continues to vie for EU membership.

This deal puts pressure on Turkey’s already overwhelmed infrastructure, while European leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel benefit politically from the drastic decrease in arrivals. Turkey hosts nearly three million Syrian refugees, having become a practical holding center for a growing population of displaced people. With terror attacks and domestic instability in Turkey on the rise, the agreement is not only politically but also legally questionable—skating international laws on refugee protection. Amnesty International calls the deal a “historic blow to rights,” as refugees are immobilized by the EU’s migration policies. And it doesn’t change the reality: people will continue to travel to Europe.

Rather than limiting the work of smugglers, Mohammad says, the deal has only made them change their routes. In the summer of 2016 smugglers sent boats to Italy instead of Greece, a longer and likely more dangerous trip. Mohammad says his trips have consistently been successful, but that’s not always the case. The IOM also estimates that nearly 5,000 refugees died making the trip by sea in 2016 alone. That toll is up from previous years, averaging 14 deaths at sea per day. The route represents one of the most perilous elements of the refugee crisis, and the demand isn’t going away. “People need me,” Mohammad says.

Although Mohammad’s work is controversial, some feel that paying smugglers is their best hope. A Syrian passport gives few other legal alternatives. Beyond documentation that would allow short-term travel for Syrians outside the country, long term options are limited to the capacity of a few organizations that struggle to process the extreme demand. Leaving Turkey requires approval from another country and since the war has escalated, all but a few countries now deny Syrians visas.

Abdullazeez, center left, shares Iftar with Syrian housemates while he rests for a night in Istanbul. Leaving Syria nine months ago, he spent $500 and over nine hours at sea to make it to Sweden. He was granted refugee status in Sweden and now travels back through Turkey to retrieve his family and bring them legally to Europe.

Limited space and expensive rent requires innovative housing for refugees in Istanbul. This lead Ali to open a hostel for Syrian men when he came to Turkey to escape violence in Aleppo. Many of the men living in Ali’s hostel came to Istanbul by themselves and rely on technology to stay connected with family in Syria.

As Syria’s neighboring countries shoulder a disproportionate load left by the EU, those who really suffer are the displaced individuals caught in the middle of the politics. For those refugees already in Turkey, the agreement offers few viable options, even for those living in desperation. This pushes many Syrians to make the dangerous trip across the sea as a last resort. Some families succeed, some fail, and others like Wafaa’s are scattered. Staying connected is now a transcontinental process.

The only time Wafaa’s family is together is during their nightly WhatsApp calls after her sister gets home from work. Breaking the evening lull, the house comes alive with the voices of family members in Germany and Syria. Wafaa and her family used to live together in Damascus but when violence escalated, they decided it was time to get out. Wafaa’s father stayed in Damascus while her brother and sister successfully traveled to Germany. Wafaa and the others tried to organize a trip to meet them in Germany but ended up stranded on Turkey’s coast. Now they’re stuck in Istanbul.

As they gather in the living room around cups of dark amber Turkish tea, Wafaa’s father tells them about high food prices and electricity cuts back home. Her sister talks about learning German and settling into a new apartment. In Istanbul, Wafaa tries to learn Turkish and searches for ways to get the rest of her family to Germany. Unless she applies for resettlement through the United Nations, an arduous and unpredictable process, options are slim.

Shams was pregnant with Abdullah when she came to Turkey while her husband travelled to Germany to apply for refugee status. FaceTime calls with Abdullah’s aunt and father in Germany are the only form of communication he knows while his parents try to gather the resources for reunification.

Ali, Hasnaa and Mazin’s nephew, crossed the Syrian border on foot after fleeing his home in Aleppo. “War isn’t the actual shooting or the battle, it’s the aftermath”, Ali says. After coming to Turkey, he tried to travel to Germany with his aunt and cousin but now remains in Istanbul. He continues to seek options for travel to Europe.

Nightly WhatsApp calls are a slice of normality for Wafaa and her family. These virtual connections are the only thing her nephew Abduallah knows of his extended family. His earliest memories of his father are images on a screen and his only conception of Syria consists of the few photos in the kitchen where he sleeps. Part of a new generation born into this crisis, Abdullah entered the world as a refugee after his mother Shams came to Istanbul while pregnant. Abduallah sleeps on a pile of blankets in the corner while Shams holds the phone camera up in view of his aunt and father.

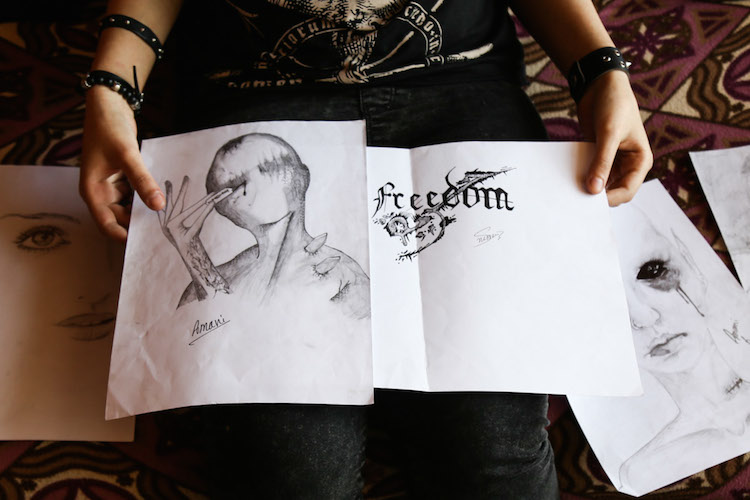

Maya and Nejla are old enough to remember Syria. In their room they point out the few things they brought with them when they left home in Damascus. But these images have slowly faded in the transition they have been living since. For a long time, Maya and Nejla say, this frustration turned into depression. They use technology to help move beyond the past, scrolling through Instagram fitness accounts on their bright iPhone screens.

In the bedroom next door, another laptop screen glows. The voice of the girls’ mother Hasnaa comes through a Skype conversation with their father Mazin and brother Tarik. Hasnaa traveled by boat from Turkey with her three-year-old daughter Sham in tow. Mazin recalls the conversation when Hasnaa told him she wanted to make the trip to Europe. She could not wait around longer. With no legal route to resettlement available, the sea was their only option for a future in Sweden.

For Noor*, another young Syrian stranded in Istanbul, the promise of life in Europe once pushed her to attempt the same dangerous journey. Now surrounded by a group of young Syrian friends who have since settled in Istanbul, she says staying is not something she would have chosen for herself. Noor left Syria with her family with the intention of staying in Turkey only long enough to coordinate with a smuggler, collect enough money, and move on.

Noor calmly recalls the many attempts and $10,000 she and her family paid smugglers to coordinate the trip. The process was far from scientific, she says, and felt much more like a nightmare. She describes being crammed in the back of trucks and taken through the night by smugglers who later threatened her family at gunpoint.

Noor’s family was ready to give up when another smuggler put the family in a small dinghy and told them to paddle themselves to Greece. When she arrived on the shore, the Greek police threw her family’s belongings in the water and sent them back to Turkey. She still wishes she could have made it to Europe, but now, her money drained by smugglers, making a life in Turkey is her best option. After so many failed attempts, it is too much to try again.

Nina, 17, waited in two years in Istanbul with her mother and sisters while applying for resettlement through the United Nations. After extreme vetting, the family finally received approval for resettlement. This is rare experience out of the many who apply.

Mazin and his family in their dining room in Istanbul. Their suitcases remained unpacked after eight months in hope they’d soon get approved to travel to Europe. “[It’s] like they are sitting in a prison,” Mazin said of the years his children spent waiting.

Meanwhile, Mazin tries hard to forget the trauma of his wife’s first failed attempt to travel to Europe. In an overcrowded rubber boat, Hasnaa left with her nephew Ali and Sham from the coastal city of Izmir. When other passengers in their boat saw the coast guard in the distance, they panicked and their boat popped, sending Ali, Hasnaa and Sham into the freezing water. After Sham recovered in the hospital, Hasnaa and her daughter made another attempt—this one successful.

Mazin had begged his wife not to try again after hearing of his daughter’s near death experience. “Sometimes I’m crying when I’m imagining the pictures, really I’m crying,” he says. After boarding a boat with her daughter for a second time, Hasnaa’s gamble paid off. She registered as a refugee in Sweden and applied for reunification to bring the rest of her family to Europe. Meanwhile in Istanbul, Mazin and his children wait.

But uncertainty is nothing new for Maya and Nejla. They now look ahead to a new life in Europe. They only wish it could have happened sooner. Maya says she envies her little sister who won’t grow up with the same uncertainty. “If you ask her ‘where are you from?’ she’ll tell you ‘I’m Swedish,’ she doesn’t know anything about Syria,” Mazin says.

The girls laugh as they watch Sham twirl on the screen behind Hasnaa wearing a frilly pink tiara before saying goodbye to their mother and little sister. The family sits together on the bed, ending their day like many others: in front of a computer screen. It was on the same screen they use to watch workout videos for hours each day where they finally saw their approval to travel to Sweden. Four years after leaving Syria, the family settles into a life of uncharacteristic stability.

For families in the same situation as Wafaa’s in Istanbul, many days still feel like a waiting game. Some are like Noor—accepting Istanbul as their new normal, while still many others choose to risk it all for the possibility of new start in Europe. Meanwhile, technology helps fill the vacuum left by forced separation. FaceTime calls replace family dinners and virtual bedtime kisses are a substitute for the real thing. These are experiences of people caught in a system in which mobility is not a personal choice. Part of a forced diaspora, they are adapting to the reality of this new normal—stuck until the system allows for change.

* Name changed to protect identity.

Betsy Joles is a photographer and student at the University of Texas at Austin. Her interest in Syrian migration lead her to Turkey to conduct research independently. She spent six months working on a documentary photo project about the Syrian diaspora, highlighting underrepresented aspects of refugee integration.