Asimba Bathy, who led the creation of Congo 50 along with Alain Brezault spoke to Warscapes about the process and reception of the graphic novel. The interview and excerpted chapter are translated from the French by Sara Hanaburgh.

Warscapes: How did this project come about?

Asimba Bathy: The Democratic Republic of Congo was getting ready to commemorate 50 years of independence on June 30, 2010. It was the perfect moment for the Congelese graphic novel to assert itself and we wanted it to be present in every conversation and debates in different social milieus and also in schools and universities.

Warscapes: Can you describe the process?

Asimba Bathy: We started by building contacts on-site in Kinshasa to help us to research funding opportunities for the making and production of a graphic novel that would be a collective work with a less suggestive title than “Congo 50”. Unfortunately, that approach proved unsuccessful.

Once we were in Brussels, the idea came up again in a discussion we were having with the directors of Africalia, and we contacted the Tervuren Museum who wanted to do something in conjunction with this celebration. At one point it was suggested that I alone create the graphic novel. But, I made it known right away that I wanted to have the participation of the team of artists I direct at BD Kin Label.

We also contacted storyboard writer, Alain Brezault, who knew Congo well and had formerly done remarkable work with the artists of this country. And they really liked him and followed his lead to get the storyboard workshop in motion.

Warscapes: How did you all collaborate and how did you arrive at a unified vision of the project?

Asimba Bathy: At the outset, we held a long briefing in order to understand the history of Congo, which we divided into chapters that corresponded to the number of participating artists - eight in total. As creator and coordinator of the project, I sent the artists out to the field to conduct their research with elders, historians, journalists, and people of all ages. We even organized a visit to the national archives, where we obtained more extensive information on different events in the history of Congo.

And Alain Brezault arrived a little later to close the deal and fill in the necessary gaps in order to make the text readable and coherent. Once again, as in 2007, with his work on the project Là-bas…na Poto, we are very grateful to him.

Warscapes: What is the story of Congo 50? What happens in La Longue Marche (The Long Journey) excerpted here?

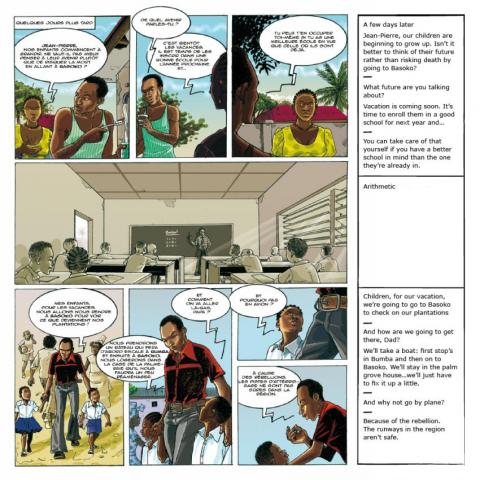

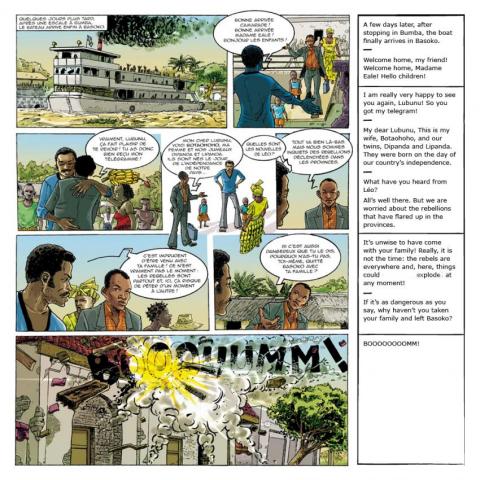

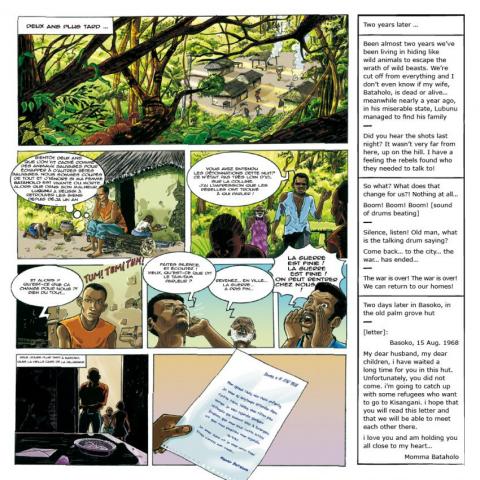

Asimba Bathy: Actually, Congo 50 is a very small part of a novel that I am currently writing which is based on a real testimonies, a lot of which I used to write three out of the eight storyboards that make up this wonderful graphic novel. The graphic novel is meant to address a wide popular audience, especially the youth, through a dynamic narrative divided into eight parts, each with six storyboards that takes us through the 50 years of independence in Congo. This half-century is presented through the lives of twin boy and girl siblings, Dipanda and Lipanda, whose names mean 'independence.' They are baptized on June 30th, 1960, the day of the birth of the Democratic Republic of Congo

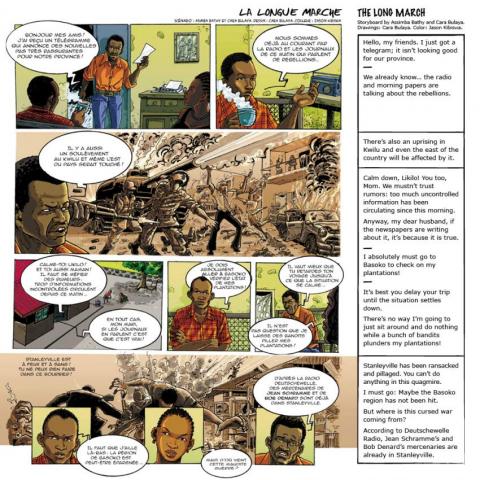

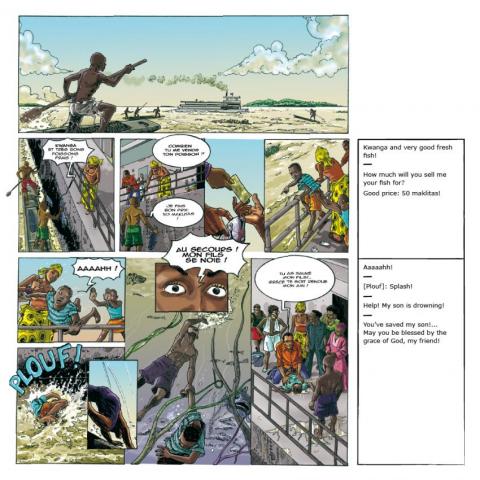

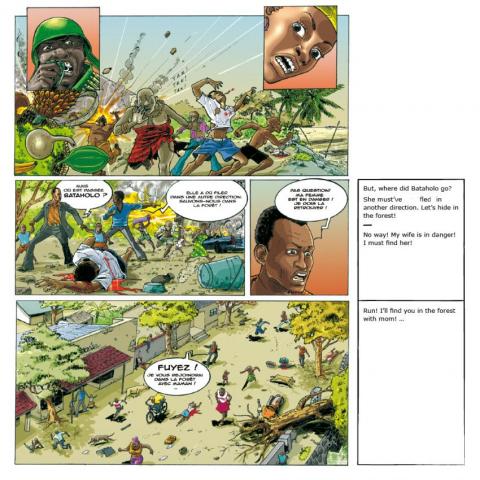

La Longue Marche by Cara Bulaya depicts the ordeal of the populations that find themselves in war situations and shows how, at times, families are separated and are often unable to reunite.

Warscapes: Why did you choose the medium of the graphic novel?

Asimba Bathy: I feel that the Congolese graphic novel is in the process of making its mark again, after a period of slack activity for more than thirty years. Any possible occasion where the medium can make its presence known is an opportunity. We ourselves, as authors of graphic novels, could not have turned to any other medium to express ourselves in a meaningful way.

Warscapes: Many people are focused on 50 years after independence in various African countries. What did you want to say specifically about Congo through this book?

Asimba Bathy: Congo’s history, fifty years after independence is obviously impossible to recount in a forty-eight page graphic novel. That is why we allude to a few noteworthy moments in the country’s history and the debates regarding what really happened in the hopes that it will help the Congolese, at least a little, to re-appropriate their own history.

Warscapes: What was the response to your work in Europe? Did you also distribute it in Congo? If yes, how was it received?

Asimba Bathy: The least one can say about this graphic novel is that it has had a welcome reception—I’d even say too well received—whether in Europe, in Congo, and in certain African countries as well, where it has been in high demand and we were able to distribute it.

Warscapes: The violence in Congo has been very brutal. How did you depict this?

Asimba Bathy: Every country in the world, especially those in the Third World, is shaken today by violence in one form or another. Opening up the can of worms that is the history of violence is just one way to say that violence is a bad thing. But, we were more focused on incorporating elements that the graphic novel genre is known for such as a great story, humor and intrigue. And at the same time, we wanted it to replicate an authentic reality. That is the reason it has been successful but it has not offended anyone.

Warscapes: Were there decisions about what was to be excluded and included from the history of the region in your book?

Asimba Bathy: There was no question that we would write a macabre history with sharp cynicism in order to present the history of our country in a very sobering way, even though, of course, many good things did happen.

Asimba Bathy was born in 1956 in Watsha and left for Kinshasa with his parents in 1966. He studied advertising at the Academy of Fine Arts and worked for various magazines and newspapers in Kinshasa. He created OAR (United Artists Organization) and BED’ART studios. In 2007, he participated in the making of a collaborative graphic novel, 'Là-bas..Na Poto' about immigration, which was published by the Belgian Red Cross and the Democratic Republic of Congo with the support of the European Union. Soon after, he launched the Kin-Label which has published 21 graphic novels so far. He also collaborated on a graphic novel, 'La bande dessinée conte l'Afrique' published in Algiers by Ed Dalimen in 2009.

Cara Bulaya Samy, known as Cara was born in Kisangani in 1973. He graduated with a degree in Graphic Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts in Kinshasa. He has worked as a graphic designer and illustrator for newspapers and for graphic novel projects supervised by Thembo Kash and Asimba Bathy. He is an active member of the Kin-Label where he continues to publish his work. He is the creator of 'La Longue Marche' excerpted on Warscapes.

Born in France, Alain Brezault spent his childhood in Congo and Tahiti. Apart from being a writer, he is also a consultant for several European organizations regarding multimedia communication and socio-cultural cooperation with countries of the South. He has conducted workshops in writing scripts for comics in Bamako, Lomé and Kinshasa for the creation of 'Là Bas…Na Poto.' He has collaborated with Africultures to create an internet portal focused on promoting the francophone graphic novel. He is the founder and host of the site, AfriBD.com produced in partnership with three African cartoonists organizations located respectively in Bamako, Kinshasa and Mauritius to cover West Africa, Central Africa and Indian Ocean.

Sara Hanaburgh is a scholar of African literatures and cinemas. She received her PhD from the City University of New York where she focused on the contemporary African novel and film (1980s to present) from the sub-Saharan Francophone region. Her work argued that as artistic responses to the human effects of economic globalization on the continent, the most extreme effects of the current “global” order reinforce notions of a sexualized, racialized or ethnicized “Other.” In addition to ongoing research, she is presently translating a novel by the late Gabonese author, Angèle Rawiri, into English. She teaches French at Fordham University.

A special thanks to Marina Brant for the translation graphics.