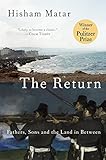

Hisham Matar’s new memoir The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land In Between is several books at once, depending on which way you hold it to the light. Any text depends on the light a reader’s gaze lends it. Yet The Return is particularly, dazzlingly multiple: memoir, geography, biography, journalism, literary criticism, and dark historical thriller.

The effect is startling in The Return’s brief 240 pages, but Matar achieves it, in part, by folding in so many other books. We can unfold many of them and pull them out, like the hidden rooms of a child’s pop-up book. Most of these rooms themselves contain further hidden spaces, which extend not just the story of fatherhood and Matar’s family, but of modern Libya.

At its surface, Matar’s memoir promises the “true” story that has undergirded his two fictions: The real Hisham Matar returns to Libya in 2012 to search for echoes of his father, the activist-industrialist Jaballa Matar. The author’s father was kidnapped in Egypt in 1989, where the family was living in exile, and handed over to Moammar Ghaddafi.

After that, Jaballa Matar was taken to the notorious Abu Salim prison. He was never seen outside it again.

This is Jaballa’s story, but his son cannot approach it directly. Its roots sink down a hundred years, into the time of Grandfather Hamed, Jaballa’s father. Hamed’s age is unknown, but he certainly came of age in the nineteenth century, during Libya’s Ottoman era, and fought the coming of Italian colonial rule. Like his son, Grandfather Hamed was kidnapped and sent off, probably to be executed. But Hamed escaped his Italian captors and fled to Egypt.

Grandfather Hamed eventually returned to Libya and built a home in the village of Blo’thaah. This was no ordinary village home. When Hisham Matar was a boy, he writes, the place seemed “as mysterious and magical as a maze.”

I often lost my way in its endless rooms, corridors, and courtyards. Some windows looked out onto the street, some onto one of the courtyards, yet others, strangely, looked into other rooms. It was never quite clear whether you were indoors or outdoors. Some of its halls and corridors were roofless or had an opening through which a shaft of light leant in and turned with the hours. Some of its staircases took you outside, under the open sky, before winding back in.

This Escheresque—or Grandfather Hamedesque—architecture is echoed in the construction of Matar’s The Return, which blossoms in dozens of unexpected ways, often winding back in to rooms that now appear different. Perhaps it was the only way of telling a story where so many of the facts have been suppressed, shredded, or hidden.

Fathers, sons, and their dreams

Parts of The Return evoke a timeless past of relationships between son and their lost fathers. It’s the third chapter when Telemachus and Odysseus first appear. Matar, like Telemachus, must endure his father’s “unknown death and silence.”

Shakespeare’s King Lear also appears, for Edgar’s speech to his blind father. Dante appears with The Divine Comedy’s Ciacco, a man who had become unrecognizable in death, just as Hisham’s father was unrecognizable, even to his brothers, in prison. “The anguish which thou hast perchance withdraws thee from my memory, so that it seems not that I ever saw thee.”

Turgenev appears twice, once with On the Eve and another time with Virgin Soil. At first, the Russian master doesn’t seem to belong here at all. But the Virgin Soil’s Alexey Dmitrievich Nazhdanov illuminates the internal crisis of many in Matar’s family in 2011 and 2012. Matar writes that Nazhdanov, whose name contains the word for hope, is trapped between a romantic sensibility “that makes him ill-suited for absolutely certainty, and a revolutionary heart that craves that certainty.”

The reader cannot be surprised to find Kafka’s The Trial, when it appears, for its tangled, repressive bureaucracy. But Matar also draws something unexpected from The Trial: the interrelatedness of oppressor and oppressed, and K’s tenderness towards to the men who come to execute him.

Matar’s own two novels also appear in the opening chapters. As he and his mother wait anxiously in an airport terminal, on the author’s first trip back to Libya since he was a boy, his mother playfully asks who is returning to Libya: “Suleiman el-Dewani or Nuri el-Alfi?” These, as Matar reminds us, are the protagonists of his novels In the Country of Men (2006) and Anatomy of a Disappearance (2011).

Although Matar doesn’t quote from his books, he still manages to tuck them up inside this narrative—even for the reader who’s never heard of them. After all, we know that the author has written two novels where Libyan sons search for their fathers’ true stories. The novels are thus seeded inside The Return, expanding beneath the surface like one of Calvino’s invisible cities.

Jaballa Matar’s writings also figure. We hear not only the messages he smuggled out of Abu Salim prison in the 1990s, but also his poetry and two of the short stories that he wrote as a university student. Jaballa’s author-son translates excerpts of the stories that ran in a June 1957 issue of a student-run journal, The Scholar. There is enough material to allow us to imagine not only the rest of Jaballa Matar’s juvenilia, but also to feel the literary journal in our hands, and the other stories it might have included.

There is a poem of Jaballa’s that he might, we’re told, have recited while fighting despair in prison. In his son’s translation: “Had the pain not been so precise / I would have asked / To which of my sorrows should I yield.”

Confines of the Shadow

There are not many serious histories of modern Libya, Matar tells us. All that’s been written on Libya’s modern history “could fit neatly on a couple of shelves,” Matar writes.

Whether or not that’s strictly true, neither Libya’s Italian colonizers nor the Ghaddafi regime were kind to writers, archivists, and investigators. The Return cannot itself build an entire history of modern Libya—there is not enough for Matar to stand on—but he folds in as much as he can. Among the texts from which he borrows are the historical fictions written by Alessandro Spina, the pen name of Basili Shafik Khouzam, a Syrian Maronite author who grew up in Libya and wrote in Italian.

Midway through The Return, Matar calls up the Arrudi Café of mid-twentieth-century Benghazi. He places Spina there, with other Libyan writers, artists, and intellectuals.

Matar doesn’t name The Confines of the Shadow epic, which Spina started writing before he had to escape, ironically, to Italy. The Confines is another multiple book. While it’s fiction, it also rebuilds the complexities and conflicts of early-twentieth-century Libyan history through a variety of genres and genre-feints. In the first book of the series, The Young Maronite, Spina weaves in quotes from colonial-era newspapers, books, and government directives, tucking more fold-out rooms into his space within Matar’s memoir.

Later in The Return, Matar circles back to Spina’s evocation of an Italian colonel in The Confines of the Shadow. This colonel is pacing up and down the Benghazi waterfront as he criticizes those who are turning Africa “into a bordello and offering her up to our young men, so that they may vent the entire spectrum of their human, heroic, sadistic, and aesthetic emotions.”

Fortunately, the first books of The Confines of the Shadow have now been translated by Andre Naffis-Sahely and are available from a Libyan publisher who, Matar tells us, was forced to relocate to London.

Not only the censor

Some books do their work in The Return just by sitting on the shelves.

As part of his research in post-Ghaddafi Libya, Matar sits with Ahmed al-Faitouri, editor of the new publication al-Mayadin. Inside al-Faitouri’s office, Matar finds books by Faulkner, Hemingway, Calvino, Camus, Vargas Llosa, and others. These authors are not used for anything beyond this mention. But as they stand there, they contend Ghaddafi’s narrower vision of Libyan history.

These authors may even have been approved by the censorship office, al-Faitouri explains to Matar. But the problem was not only the censor. The regime’s repeated assaults on bookshops—confiscating their stock and closing some down—meant that it became practically very difficult to find books in Libya, even those the censor permitted. If The Return is not just a history of modern Libya, but also a simulacra of a living modern Libya, then Matar continues to stand against the regime by seeding the shelves with great literature.

Another important book that stands against the censors is Danish journalist Knud Holmboe’s Desert Encounter: An Adventurous Journey through Italian Africa (1935). Matar borrows a long excerpt from Desert Encounter to describe one of the concentration camps where Libyans were held by Italian forces: “It contained at least fifteen hundred tents and had a population of six to eight thousand people.”

Holmboe’s book was banned in Italy. Matar also tells us of Holmboe’s murder, in which Italian intelligence officers were likely involved.

There are not only Western books in Matar’s construction: The Qur’an figures in many places throughout, expanding the reader’s sense of Matar’s family and the Qur’an itself. But as we pass from room to room, there is a surprising absence—there are few women’s books to be found. Among all the densely networked books and poems, Jean Rhys may be the only female author. There are important women present in The Return: Matar’s wife Diana, his mother, his aunt Zaynab. But these women’s arts are visual, gustatory, caretaking, aesthetic. They do not write books.

Another time without books: Chasing Saif

There are far fewer books and poems after we reach chapter 17, where we begin a dance with the Libyan dictator’s eldest son, Saif al-Islam Ghaddafi. The chapters here become long rooms that we race along, chasing down Saif and his cronies, knocking through doors, tripping over thresholds in our desperate, thriller-like need to know what Saif might know.

In the end, Saif blocks us, throwing up a final, impenetrable wall. We stand there, knocking our head against it, as Matar returns again to Libya. Again, after Ghaddafi’s fall. We return to a family home, among death and uncertainty.

In the end, Matar takes us back to Telemachus’s words. As he does, we are back where we began: “I wish at least I had some happy man / as father, growing old in his own house— / but unknown death and silence are the fate / of him…”

We see the words differently now, or at least Matar does, and we must follow him. This is image of a son waiting for his father has defined him, hemmed him in. Can he now create a door to exit this house?

The last text

Abu Salim prison is where Jaballa Matar most likely died in 1996, seven years after he was kidnapped in Cairo.

It is this prison that provides the final embedded text. The last book isn’t a book, but a folded piece of white linen that the author’s Uncle Mahmoud smuggled out of Abu Salim prison, where he once had a cell not far from his elder brother Jaballa. The linen was part of a pillowcase, but Mahmoud picked out the threads until it became a sheet onto which he wrote poems and quotes and notes, “possibly the only surviving literature from all the countless volumes that have been authored inside Abu Salim prison.”

We already know Uncle Mahmoud as the lover of The Brothers Karamazov and Candide and Madame Bovary. He continued to love and discuss these books in prison, as a form of resistance.

This text—also a powerful resistance—was folded into a strip and sewn into the waistband of his underpants so it could be smuggled out. As the author examined it, he tells us every inch had been written on. This single sheet contained multitudes. Perhaps these were only tiny fragments, and yet they are also were an infinite possibility of words wedged between words, between words.

Feature image: "Relativity" by MC Escher.

M. Lynx Qualey spends her time squinting at the in-between spaces of literary translation: who's in, who's out, and why. Most often, she writes about what happens to Arab and Arabic literature in translation, and she blogs daily at http://www.arablit.org. Twitter @arablit