“The people must know before they can act, and there is no educator to compare with the press.” —Ida B. Wells, 1892.

Ida B. Wells, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing slightly right, 1891. Image via Library of Congress.

Revolutionary investigative journalist, black and women’s rights pioneer, Ida B. Wells, was born 153 years ago today. Wells fought against oppression early in her life, her experiences sparking her career switch from educator to hard-hitting journalist, ready to expose the truth. Wells co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) along with civil rights activist and historian, W.E.B. Du Bois. The NAACP was founded, in part, as a reaction to the practice of lynching, which Wells began exposing 14 years earlier. However, the primary white leadership proved problematic for Wells—who did not believe the institution could work to address increasingly difficult racial problems. She left the NAACP and founded the Negro Fellowship League as a way to aid black men who wanted to move to Chicago. In 1896, 13 years prior to the founding of the NAACP, Wells helped found the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) along with abolitionists, Harriet Tubman and Frances Harper, and civil rights activist and suffragists, Mary Church Terell. The group was organized in response to a Southern journalist’s attack on the character of African-American women. Widespread lynching, an increase in segregation, and the determination to raise the spirits of African-American women also contributed to the founding of the NACW.

“No nation, savage or civilized, save only the United States of America, has confessed its inability to protect its women, save by hanging, shooting, and burning alleged offenders.” —Ida B. Wells, 1900. Lynch Law in America

Image via Biography

Before Ida Wells became a founder for organizations, she used extraordinary investigative skills—her work previewed human rights investigation and statistical analysis. After three of her friends were lynched in Memphis in 1892, Wells attacked lynching in her newspaper, Free Speech. She wrote a scathing editorial, attacking the lynch mob who murdered her friends and unmasking the South’s justifications of lynching. An angry mob, incited by the article, destroyed the Free Speech offices and threatened Wells’ life. She moved to New York where she continued her lynching investigation, writing for the New York Age, an African-American newspaper. Wells looked into the charges given for the lynching, discovering that blacks were lynched for failing to pay debts, being drunk in public, and competing with or appearing to defy whites. The South stated that the assault or abuse of white women by black men was justification for lynching of black men—which Wells found to be generally untrue:

“… the South is shielding itself behind the plausible screen of defending the honor of its women. This, too, in the face of the fact that only one-third of the 728 victims to mobs have been charged with rape, to say nothing of those of that one-third who were innocent of the charge.”1

She discovered that black men were sometimes lynched because they had affairs with white women—not because they raped them. Wells received funding for her investigations from political activists in New York City, whereupon she published her findings in a pamphlet, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in all its Phases. The Women’s Loyal Union of New York and Brooklyn was one institution that “helped to organize a testimonial for Wells in Lyrics Hall in New York City to raise funds for her cause.”2 Wells dedicated her anti-lynching pamphlet to the “Afro-American women of New York and Brooklyn… [who] made possible its publication.”3

Ferdinand Barnett, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and their Family, 1917. Image via Blackpast.

“There is therefore only one thing left that we can do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.” — Ida B. Wells

Long before Wells became a journalist, she graduated from Shaw University after passing the teacher’s exam and soon became part of the small Memphis community of educated, middle-class African Americans. In 1884, Wells was forced to leave the “ladies car” on a train in Ohio after she refused to move and sit in a car for blacks. She hired an African American lawyer and won $500 after she filed a lawsuit against the railroad. However, the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the decision three years later. The injustice she suffered led her to campaign for black rights and anti-lynching laws. Her career in journalism began at The Living Way, a Memphis church newspaper where she wrote under the pseudonym “lola.”

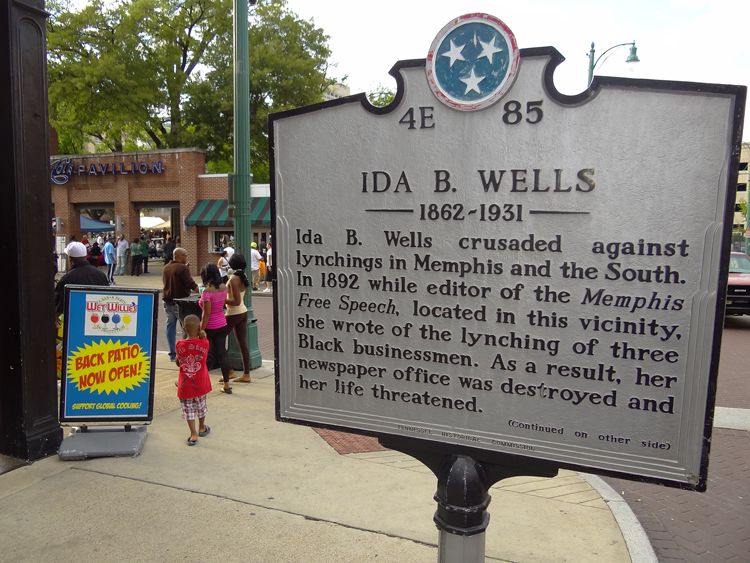

Sign Commemorating Ida B. Wells, Downtown Memphis, 2012. Photograph by Adam Jones. Image via Flickr.

Although Wells was unable to see anti-lynching laws pass during her lifetime, her efforts aided three important aspects of modern life: black rights, women’s rights, and investigative journalism. Wells campaigned alongside important human rights leaders including Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony. Wells refused to be treated as a second-class citizen and never backed down from exposing the truth, writing that lynching was, “an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized.”4

Ida B. Wells-Bartnett Museum in Holly Springs, Mississippi, 2014. Image via Facebook

In 1989 PBS’ The American Experience aired a documentary about the journalist, Ida B. Wells: A Passion For Justice. The documentary features award-winning author Toni Morrison, Wells’ descendants, and includes commentary by historians, accompanying photographs of Wells, newspaper clippings, and drawings. Watch A Passion For Justice below:

Endnotes

- Ida B. Wells. Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, 1892.

- James P. Danky and Wayne Wiegand. Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 2006. p. 14

- James P. Danky and Wayne Wiegand. Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 2006. p. 23

- Bernestine Singley. When Race Becomes Real: Black and White writers confront their personal histories, 2002. p.125

Feature Image: Ida Wells-Barnett plaque, Extra Mile: Points of Light Volunteer Pathway, Washington, D.C. Photo by artstuffmatters, 2010.

Asiya Haouchine is an intern at Warscapes. She is an English and Journalism major at the University of Connecticut.